Daily, snackable writings to spur changes in thinking.

Building a blueprint for a better brain by tinkering with the code.

subscribe

rss Feeds

SPIN CHESS

A Chess app from Tinkered Thinking featuring a variant of chess that bridges all skill levels!

REPAUSE

A meditation app is forthcoming. Stay Tuned.

SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS & CURIOSITY

August 20th, 2020

Our current state contains subtle clues about what needs to change in order to get where we want to go. This isn’t just true literally, as with location but figuratively: it’s the underlying implication of all areas of life:

If only I could notice the right details…

If only I could see the signal in all this noise..

If only I knew exactly what to pay attention too..

The nature of realization is a subtle alignment of pieces that illuminate a particular structure binding and relating them all. Before realization, these pieces float among one another, perhaps with only vague association - that association being that they are all aspects of the issue that has created so much confusion.

Our experience of confusion is generally regarded as negative and unpleasant. It’s bound up with frustration and impatience. But confusion is one side of a rivalnym - a term coined here on Tinkered Thinking to identify a pair of words that refer to the same thing, but in opposite or rival ways - similar to both antonyms and synonyms.

Confusion describes our experience with a subject that we don’t fully grasp nor understand.

But so does curiosity.

Confusion is the unpleasant negative version of this experience and curiosity is the desirable one. The different ways we experience this unknown are so drastically different that we scarcely ever notice that we are referring to the same thing - the unknown.

This pair of rivalnyms also contain another important complement which unravels the core of their differences: one is externally focused, the other is internally.

At first pass, we might think both these words are externally focused - they both deal with a subject outside of our selves. But what exactly is confused when we find a subject confusing? The assumption is that it’s possible to make sense of the subject, so the subject is not inherently confused, otherwise we probably wouldn’t be spending time trying to figure it out. The confusion has more to do with our own state than it does the issue at hand. We can easily fit curiosity in to the same rubric. We are curious. The subject might also be described as curious, but it’s still reflexive: the statement describes something about our state.

The internal - external distinction is either a bit more subtle or maybe a bit of a stretch. The experience of confusion, as typified by frustration is an assessment of our own self.

I can’t get this,

I don’t understand this,

Am I stupid?

Frustration is an inwardly focused activity. And it’s also a dead end: the answer we are looking for does not lie within an assessment of our own abilities, it lies externally, in the details we are studying and an invisible way they are connected that has yet to click.

Curiosity on the other hands is the exact opposite. When curiosity is running high, we often forget our own self completely. We get lost in the details, exploring them, toying with them, playing. The focus of curiosity is external, and this is despite the fact that we probably don’t yet understand exactly what we’re dealing with, otherwise, why would we be spending time with the topic?

A subtle equation emerges when the pieces are framed in this way. When patience is added to frustration, curiosity emerges. But what exactly does that mean? Aren’t frustration and patience just antonyms? Is this supposed to mean that the default state is actually curiosity and we just screw it up by adding impatience and frustration? Well, yes. Impatience and frustration in the context of something we don’t understand occurs when our own self gets in the way. We abandon an interest in the situation to become focused on the nature of our own incongruity with the situation.

Appropriately though, we get in our own way when we become overly concerned with a sense of self - an identity, a concept of who we are as an entity that can and can’t understand something. Perhaps, we can make a bit more progress and have a bit of fun during the process if we let go of our sense of self a little bit.

THE TINKERED THINKING BOOKSTORE

August 19th, 2020

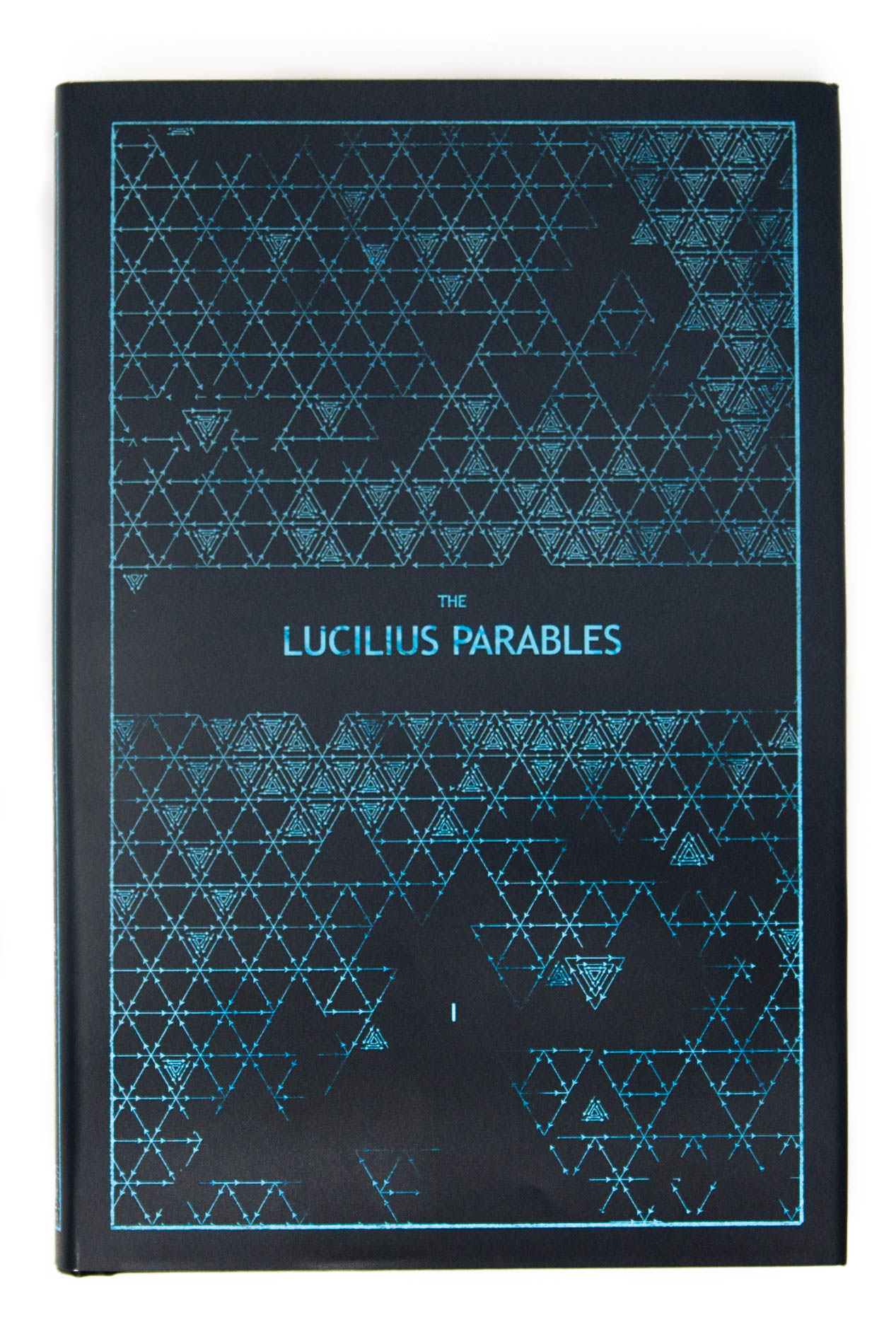

Earlier this week, The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore was launched with purpose of making The Lucilius Parables, Volume I available to readers and listeners for purchase.

Tinkered Thinking was responsible for just about every single aspect of this book. The writing, the typeset, the art design, the illustrations…everything.

Even The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore was also coded from scratch in-house. Other than the work of a professional editor hired primarily for proofreading and of course the actual physical construction of each book and mailing, every part of the reader’s experience, from awareness through the podcast, the website and twitter, through the purchasing process and all the way until the last page has been turned, all of this was done in house.

The purpose of going through the sizeable effort of building an online store from scratch has to do with economics. Platforms like Shopify offer the ability to quickly set up an online store, but of course these stores are usually a minimum of $30/month. This isn't much, but an upgrade of the ‘look’ of the store can be a couple hundred dollars, and with time, the cost of playing a ‘long game’ with a product over a couple years starts compounding, because who knows, it might take another year or two of exposure before something takes off. With a platform like Shopify, that time is going to cost, meaning there’s a financial downside to running a long experiment that doesn’t go immediately well. The more time with available exposure, the more potential upside the project is exposed to. The Bookstore hosted by Tinkered Thinking drops all of these costs to tiny fractions. While the sale of a single volume of The Lucilius Parables doesn’t yield much profit due to high print-on-demand costs, it’s enough to cover the running costs of the online store for a couple months, unlike a platform like Shopify which would require the sale of several books to cover the cost of a single month.

The whole aim with every piece of this project has been to create an automated hands-off system that costs next to nothing to run, in case no one is interested, and then instantly generates a profit once a purchase is made. This asymmetry of low cost and potential benefit has the best chance of allowing Tinkered Thinking to grow in interesting ways. If Tinkered Thinking became a project motivated by money in order to survive, not only would this influence the content in potentially negative ways, but that’s also just a situation that I have no interest in dealing with personally. This setup is designed not so much with profit in mind, but in order to keep personal curiosity completely unhindered while giving readers the chance to own a beautiful piece of Tinkered Thinking. In its own small way, this is an attempt to create a non-zero sum business situation that has as little possible downside for all parties, be it reader or Tinkered Thinking.

These lofty considerations aside, it’s also perfectly realistic to say that The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore is an experiment in the market viability of the Tinkered Thinking audience. This is an important measure that is often ignored when it comes to art like fiction. Economics and all things money are often ignored by artists as something grungy, cheap and shallow, but money can function as a very important thermometer. It’s a mechanism for communicating perceived value. And as obvious as that might sound out loud, and as much as the starving artist might bitterly scoff at that point, it is an avenue for understanding the way people perceive: which is the main concern of art. While it perhaps comes out best when art is done for art’s sake, art in complete isolation is meaningless. Even the starving artist secretly hopes their work will adorn the walls of the wealthy at some point in the future, be they alive to enjoy it or not. To ignore the signal provided by money is to ignore information that can help us understand people more. It does not mean we must bend our art to boost that signal, it means that we can investigate the possibility that our art might be landing as a false negative. Lack of profit doesn’t necessarily indicate something fundamental about the art itself, but it does indicate the possibility that people can’t see the fundamental point of the art.

Low-cost experiments as provided by technology like print-on-demand and in the case of Tinkered Thinking, an incredibly low cost online store enable an artist or creator of any kind more room for experimenting with the connection between the reader, the listener and the content being created.

This asymmetry of low risk and high potential reward simply makes it more likely that a creator might tap into a virtuous cycle with their audience that in turn allows even more room and freedom to explore the process of their creation with a greater range of curiosity.

You can check out the Tinkered Thinking Bookstore and the First Volume of The Lucilius Parables at tinkeredthinking.com/bookstore, or check out the links on the main website.

PRINT-ON-DEMAND

August 18th, 2020

Tinkered Thinking recently released its first book, The Lucilius Parables, Volume I, which is available for purchase on the Tinkered Thinking Bookstore. This episode seeks to describe the thinking and the process that went into the creation of this book.

The production of this book as a physical object was a very important concern: it was important from the beginning that, if listeners and readers of Tinkered Thinking were going to spend money on a book, it had to be a beautiful book. So how does this go from an idea to a real, physical product?

One could send off the manuscript to publishers. Rejection is likely, and then many decisions about the look, feel and design and editing of the book are probably yanked out of the author’s control. Luckily, times have changed.

The tools available now to authors make the gatekeepers of traditional publishing far less powerful than they once were. As de facto purveyors of ‘good fiction’ the reading public has been at the whim of such opinions, and authors have had to bend their writing, whether consciously or unconsciously to the confines of these opinions. After all, what is more iconic for the aspiring writer than rejection by an editor who holds all the power?

Interestingly, it appears these gatekeeping positions arose due to technological circumstances. The nature of printing, particularly as books became mass-produced commodities squeezed the decision about ‘what to print’ into a centralizing function. Because mass-production requires a fairly large up front cost in order to make long term gains, this structure quite naturally silos writers from large exposure, unless of course their content fits through the filter of a publishing house and it’s myriad editorial opinions, fuelled and protected by their financial ability to actually print books at scale. This is, quite frankly, a bit ridiculous if you think about it. How is it that one editor’s opinion can predict the commercial voraciousness of a reading public? Do we not have a bunch of lovely examples showcasing just how off such editorial opinions can be? Can anyone recall how many publishers passed on J.K. Rowling’s work before she finally got a book printed?

It’s fascinating to reflect on the ramifications of these technological constraints around printing. For example: why is it that the average adult doesn’t write more? (emails, memos and corporate bullshit most certainly do not count, let’s be real). And yet most adults in the modern western world have been crammed through an education system that continually tries to extract some writing from these people. How is it that so few people adopt a serious writing habit after so much training?

Could it be that the training is influenced by a trickle down of authority from the same gatekeepers for the printing world, including of course newspapers, academia and all other print media? This is perhaps a stretch, but it’s curious to wonder what would have to change about writing education in order for more people to continue writing throughout life. Would it perhaps require less focus on the opinion of readers, aka. Editors and graders, and more focus on the potential benefits accrued by the writing mind freed from such external opinions?

Montaigne invented the Essay, and the word merely means try. To write an essay is to simply try and do something. Is it not counter-productive to proactively apply an opinionated rubric to such an attempt? Do we limit our ability to find new structures by doing so?

The questions of this tangent about gatekeepers is not intended nor explored as an affront to editors, publishing houses and English teachers. It’s merely to explore questions that have not been asked and to proffer a possible reason why the art and utility of writing is so constipated: technological and economic constraints regarding printing at scale have burdened just a few people with the task of assessing writing worth reading, when really, the entire reading public would do a far wider, faster and efficient job with the task.

The deeper purpose of these questions is that they can now be answered. The advent of print-on-demand books removes the traditional gatekeeper and links the writer directly with the reading public. While traditional publishing houses might raise their noses at such developments for allowing less-than-superior content to pollute the reader’s sphere, such individuals are analyzing the situation from the wrong angle. With a direct line between creator and consumer, the chance for product-market fit raises to an unfathomable level because the feedback loop for improvement is finally closed. Editors and publishing houses represented a blockage in this loop that has been justified by the false supremacy of someone’s ‘better’ opinion. The unfortunate reality is that an editor is just one reader. Writing no longer needs to pass through that single gate anymore.

Print-on-demand also has some other benefits. The start up cost to experiment is practically nill compared to a first run of a mass-produced book. This, again raises the chances for product-market fit as more writers can toss content out into the reader sphere to see if there is an audience for it.

This process of print-on-demand also wastes far less material than a book that is mass produced and never sells. It’s a somewhat pathetic cultural image for someone to have a closet filled with several thousand copies of their book which, never sold. Print-on-demand changes this drastically. Writers can now create experiments with content for possible audiences with very little up-front cost and minimal waste if the experiment is a dud.

The one notable downside to print-on-demand is that each individual book is quite pricey. This is the case with any new technology, especially disruption technologies. The first cell phones were suitcase-sized monstrosities that barely worked and were so expensive only the Gordon Gecko’s of the world could have them. Now everyone has a super phone that is lightyears beyond those suitcase bricks. This is the probable future of print-on-demand. As the technology scales, the individual print-cost of each book will most likely go down. There is huge incentive to do this from every angle of the situation. Competing print-on-demand services want to offer the better product at the lowest cost to potential authors, and authors, believe it or not, would actually like to make money. With so much of the control placed in the hands of the author, and the sizeable potential upside paired with practically no downside, the traditional publishing route doesn’t even look worth the bother anymore.

This nascent technology does place quite a bit of control in the hands of the author, and for some it may be too much. The first Volume of Lucilius Parables released a couple days ago required a few months of iteration, ordering a copy, waiting, seeing the result, making a change and then repeating the process. Each print-on-demand company has their own structure for getting words and design into the form of a book, and to be frank, there is an enormous amount of room for improvement here.

The first service used to print this book was a company called Blub which delivered a very underwhelming product. There were other options, like Ingram Spark, and then there was Lulu. As fate would have it, half way through this project Lulu deployed a massive upgrade to their website and suddenly carried a much larger selection of sizes and formats. The Lucilius Parables was pulled from Blurb and completely reformatted for one of the options carried by Lulu. And to get into the nitty gritty of just how different such print-on-demand platforms are, Blurb had a fantastic software called Bookwright which made book design quite smooth and relatively quick. Lulu on the other hand requires very specific PDF files that are then mapped on to the book. This requires another design program, like Adobe’s InDesign. While Bookwright with Blurb was free, the design tools required to make excellent looking PDFs for Lulu can be pricey. On top of this is an issue of translation. There was an infuriating discrepancy between the alignment of graphics in the PDF for the cover and what actually turned up in the mail. It required a painfully frustrating and somewhat expensive trial-and-error process of ordering book after book until it was clear exactly what the translation discrepancy was, which was then accounted for with a slight redesign. So while Blurb had the better formatting software, the product they deliver is entirely unimpressive, meanwhile, Lulu produces an absolutely stunning physical product, but formatting the files for the book perfectly is tedious to a degree that really does challenge the spirit. This being said, Lulu is clearly hustling to improve their platform and they’ve specifically mentioned a rollout that would solve the discrepancy that caused so much headache with the design of The Lucilius Parables.

Further, Lulu has their own bookstore, and then they also offer a decent API which can be integrated into an online store and this is exactly how The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore works. Another catch, however, is that if an author desires global distribution, meaning the book can show up in Amazon or a large physical book chain can order it, then prices go up by quite a bit, which either cuts profits drastically or makes the book rather expensive. Naturally, this is something Lulu has done quite deliberately in order to make money. Most authors who self-publish probably imagine their book in Amazon. Setting up an online store, like Shopify, or doing something completely from scratch like The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore requires an entirely different world of considerations. Luckily for Tinkered Thinking, the specific combination of a custom built online store threads the economic needle to price the book somewhat reasonably.

Such print-on-demand services also take care of all the shipping, which is factored into the price of the book when purchased. For the Tinkered Thinking Bookstore, this is another aspect of the Lulu API, which fetches the different shipping levels and costs based on shipping address. While this adds a few more bucks that seem invisible on a store like Amazon, it removes a galaxy of headache from the process for an author.

This combination of tools has enabled the entire process of ordering, printing and delivering a copy of The Lucilius Parables to be 100% automatic. Granted, it required an enormous amount of work to create The Tinkered Thinking Bookstore, which will be thoroughly covered in the next episode, but now that all is set in place, the only effort I personally have to make at this point is looking at my phone when the Tinkered Thinking Bookstore texts me the order details of a purchase someone has just made, everything else, is now completely automated.

THE LUCILIUS PARABLES, VOLUME I

August 17th, 2020

Tinkered Thinking has released its first book, The Lucilius Parables, Volume I.

Those who are regular readers or listeners of Tinkered Thinking will know that a short story is released every Sunday. These stories are dubbed ‘parables’ and they always revolve around the same character: Lucilius. This first volume is an illustrated collection of the first 51 parables released on Tinkered Thinking (along with one unreleased parable exclusive to the book).

The name Lucilius was inspired by the famous Letters of Seneca, or as they are sometimes referred to The Moral Letters to Lucilius. This is a collection that documents one side of a correspondence between the philosopher and statesman Seneca and a financial official in Sicily. Lucilius’ side of the correspondence is not included, and so he remains a bit of a mystery, appearing only as Seneca imagines him.

At the time when Tinkered Thinking was just starting, Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s work was also on the chopping block, and his use of the fictional character Nero to illustrate certain points inside of his non-fiction work helped provoke this notion and question: would Tinkered Thinking benefit from fictional narratives that try to explore the same material in a totally different light?

Even with a good deal of experience writing fiction, this is a fairly tall order: to write a short story every week. Luckily, the word ‘parable’ comes into quick and elegant use for this issue. A parable is a simple story used to illustrate a moral or spiritual lesson. And of course this comes from the Christian tradition, as they were told by Jesus in the Gospels. This concept of a ‘parable’ does several things which are in-tune with with a possible answer for that question posed about Tinkered Thinking benefiting from fictional narratives.

In literary circles, a story that blatantly demonstrates the ‘point’ that it’s trying to get across is frowned upon, especially if it’s a moral one. Why this is, and whether its good or not is a can of worms better left for someone else to crack. But a parable straddles this issue quite nicely. A parable makes no claim to be any kind of high fiction. There is something far more humble about a parable. The entire concept lacks the stuffy conceit that is often associated with fine literature. And for good reason: when it comes to the task of understanding what’s going on, the barrier to entry is far lower than it is for something like say… oh, James Joyce’s Ulysses.

This conscious flip of purpose is quite interesting in a modern context of social feeds and over-stimulation and constant distraction. Whether it succeeds on Tinkered Thinking or not, the concept of a modern parable teases at something that is both accessible and thought-provoking. These two concepts don’t usually go hand-in-hand. What is accessible is often shallow, and what is thought-provoking- or rather what is culturally deemed ‘thought-provoking’ can often be concealed within layers of obfuscation that one is required to sift through. The Lucilius Parables from Tinkered Thinking seek to cut this cake and keep it too. The kernel curiosity that generates each story is this: is it possible to help a reader think about their experience of being alive in a new refreshing way within the bounds of just a couple pages of fictional story?

Tinkered Thinking has now released over one hundred Parables, and the feedback emphatically answers: yes, It is possible.

Once Tinkered Thinking had its first birthday and about 50 parables had been written, a particularly insidious thought came floating along: there’s quite a few of these stories now.. I wonder what it would look like if they were all dropped into the same word document? Is that enough for a book?

The answer is obvious of course. To be perfectly honest, this book was written by accident. The aim was never a book, but always a curiosity about what might be possible with enough process and practice.

The 52 illustrations were added for several reasons. One is that a few parables really are quite short, and to be frank, this presents an awkward situation regarding spacing and design within a book. The illustrations provide a beautiful punctuation between each story. The other reason is that.. well, everyone loves pictures in a book, and do be sure, these illustrations were quite a lot of work. The hope is these illustrations add a bit of mysterious value to a physical item like a book. This isn’t just a bunch of stories, this was designed to be a larger aesthetic experience, like a book you can imagine having on a coffee table, but if picked up and genuinely perused would quickly have your brain bent in an unexpected and refreshing way. That’s another aspect of this book: the stories can be read in any order, and they are quick, bite-sized meditations.

Each parable in this book (aside from the one written exclusively for the book) can be found on Tinkered Thinking in its rough unedited form. But, good luck finding them in a way that is as effortless and pleasurable as turning a page and seeing a hand drawn illustration to invite you into the next story…

A LUCILIUS PARABLE: WINNOW

August 16th, 2020

Lucilius walked into the meditation hall where dozens of students sat with perfect postures, their seating spaced evenly, graphically across the floor. He scanned the faces, seeing that most of the students were well experienced, having seen them many times before for months and years. There was in fact not a single new face or anyone that he did not recognize. He had lessons ready, of course, well-oiled on the rungs of his mind ready to iterate for this particular day, but as always, he merely observed the ebb of thought, the flow of concept constructing itself in his consciousness, ideas unravelling their full bloom and collapsing to other notions, a shifting mosaic of word and feeling feeding on memory and imagination.

He took his seat, and took a slow deep breath. The class of students followed in his rhythm. He did not say anything but lightly tapped a bell near him to indicate the beginning of the meditation and then he closed his eyes along with the rest of the class.

Lucilius followed that invisible bubble, sifting into him and filling his lungs, rising his chest and then fleeing again as he breathed out. He maintained a near perfect awareness of his breath.

And then, a few minutes into the session, a car alarm in the parking lot began to blare its whine. Lucilius studied the sound as it came to him and with it he continued to feel his breath, the weight of his body, the temperature of his skin, the pulse of his heart, and with it the shifting of some students.

The car alarm continued, and then a jackhammer started up where a portion of the parking lot was being worked on. Lucilius welcomed the rigid sound, stamping in the spaces between the car alarm, all of it flowed into his sense of being as he witnessed the arrival of breath and it’s leaving.

The obnoxious sounds continued, and Lucilius could hear the unease throughout the room, the shifted seatings, the exasperated breathing. And then rather suddenly and quickly, the heat in the room began to rise. Within minutes beads of sweat were streaming down Lucilius’ face, and stressed sighs sounded from his body of students. He could hear a couple of them mutter and a few got up and left the hall as they were of course, free to do.

After this, a disgusting odour began to fill the meditation hall. Lucilius heard a few of the students gag, and then more got up and shuffled out.

And just when the heat and the smell could not get worse, the sprinkler system went off and everyone still in the meditation hall was suddenly pelted with freezing water. A few students shrieked and cursed, and ran from the hall.

Lucilius felt the icy water sap the heat from his skin. He felt the quiver of his body wanting warmth, but he merely breathed and focused on the sensation of cold, inviting it into his mind, trying to notice every last detail of the pain.

Then the bell rang. Lucilius opened his eyes and there was one student left, sitting with good posture in a corner of the hall. The student’s eyes opened.

Lucilius smiled. “You are done,” he said. “You will no longer meditate here with me.”

The student merely listened, still sitting, drenched in cold and stink. “You must go,” Lucilius said “…teach others.”

The student stood and then bowed to Lucilius and then walked out of the hall.

As for Lucilius, he got up and walked in a different direction. He had to thank his assistant for orchestrating all of the distractions.

-compressed.jpg)