Daily, snackable writings to spur changes in thinking.

Building a blueprint for a better brain by tinkering with the code.

subscribe

rss Feeds

SPIN CHESS

A Chess app from Tinkered Thinking featuring a variant of chess that bridges all skill levels!

REPAUSE

A meditation app is forthcoming. Stay Tuned.

SUBTLE LANGUAGES OF VISION

January 2nd, 2021

The golden arches of the burger franchise McDonald’s is the most recognizable symbol in the world. We compute the meaning of those arches on sight far faster than we do the word “McDonald’s”, and this is true of all symbols which also have a name spelled out with letters. We might recognize the golden arches faster than Nike’s swoosh, but we register that swoosh far faster than the name “McDonalds” when it’s spelled out as a word.

This is a lost utility reminiscent of hieroglyphics that has returned in a primitive way with brand symbols and emoticons. The use of symbol, shape, and color creates a shortcut within thought. That is, of course if the association is already present. Drawing a random, never-before-seen symbol is as useless as looking at a single letter in a foreign alphabet, but unlike most letters in alphabets, the symbol can take on a complex meaning.

Now while the golden arches don’t implicitly convey anything that might possibly lead someone to think the name “McDonalds” without prior association, we do operate with a subtle language of vision when it comes to shape and color.

One example regarding color is how fast we can find and match it. Given two instances of color within a sea of colors, the human mind can pick out the two with astonishing speed. The same cannot be done with two instances of the same word. This fact of the brain is something we have done little to utilize. Now before the digital era, this lack of capitalization is understandable: producing color in the physical world is expensive and laborious. But in the digital world, a color is just a tiny snippet of code which can be reproduced infinitely.

And so it goes to wonder what subtle use of color we have failed to tap into given all the flashy apps out there. Color seems to be used in only the most superficial way, as a means to just get some attention, as opposed to being a conduit for attention to be guided along intuitive paths.

The cluttered complexity of letters and words may also ignore something intrinsic about the use of shape that we aren’t using. As with those golden arches, or that swoosh, it’s not the color of the symbols that is conveying the information, it’s the shape. How much information are we inefficiently parroting with words that could be fast tracked with a wider more thoughtful array of symbol? The explosion of emoticons perhaps hints at the huge potential here. They are presented with no description, and yet they are used with little to no confusion. Perhaps we should take the smilie face a little more seriously and learn from it’s lesson in order to expand the way we communicate with one another.

MEMORY & CHOICE

January 1st, 2021

You are only who you repeatedly remember yourself to be; or, who you choose to be otherwise.

We remember the past in a warped way. There are strange and very unsettling opportunities when the brow furrows at ironclad evidence that the past unrolled in a very different way than we seem to remember. We bend and dress the past, and from that dolled-up amalgam, we have a story about who we think ourselves to be. This can be a severely painful story, or it can be a glossy version sugared over. The later is bound to benefit from humility, but the former gains to benefit from a rebellion: against the past, against one’s own conception of self.

This is a very difficult feat to pull off, and unlike the flashy examples of movies and video games, it does not happen all at once. Overnight changes occur only when great force is available, like with a military coup. And even that sort of force takes quite a great deal of time and effort to amass. No, rebellion on a personal level is pure subterfuge best carried out with a methodical strategy. One of the worst aspects of the mind, is also one of the easiest to take advantage of: It’s a terrible master but an excellent servant. If that servant can be put to work on a slow rebellion, the master can be gently overwhelmed by a changing mental circumstance, given enough time and consistent effort.

Take for example this very short list of excellent activities to help change one’s life: love thyself, meditate, exercise.

Now in that order, it’s a very difficult list to pull off. It would certainly be nice to feel more compassionate for one’s self, but how is that trick pulled off? If the list is reversed and priority repined in that order, it creates a long term subterfuge with greater self-compassion as the inevitable goal. Viewed on timelines, self-compassion is the longest to work towards. Exercise, on the other hand is something we can experience subjective benefits from almost immediately. Meditation on the other hand takes a bit more time: a minimum of three to four months. The larger point is that one can enable and lead to the other. A good workout session can supercharge one’s mentality - but only for a short time, but long enough to take advantage of the change, and perhaps get that meditation session in before the boons of acetylene and all other endorphins wear off. If that dual-enabling pattern is followed for enough days in a row, eventually, the benefits of meditation begin to come online, and these persist with far more reliability and endurance than the short positive kick delivered from exercise. Then, with enough peace in the mind, and time to explore that peace, self-compassion arises as a natural result.

Each part of the process piggy backs upon the prior in order to feed the overall system in a way that eventually has the most impact possible. Exercise can function as the thin edge of the wedge for this sort of process, but it need not be the only entrance to the avenue.

Regardless of what hopscotch levers are pulled to make long term change happen, the result occurs slowly because the passing of time slowly allows us to remembered a new person, one that we have chosen to try and become. The past can be an excruciating weight to bear, but we always have the tool of the present on hand, a tool which can be used to slowly steamroll the power of the past, now a palimpsest, written anew with the memory of a different person.

STICKY MIND

December 31st, 2020

As people age, they tend to be more reticent to the adoption of new ideas and beliefs that might displace the ones they already have. The mind has a fickle stickiness with respect to new ideas. While young the mind is sticky for anything and everything: as children we don’t know how the world works so almost anything can stick to the young mind.

Meanwhile, the quality of stickiness of the mind in later years seems generally coalesced in power upon the ideas and beliefs already there. The overall stickiness factor seems equal, just distributed differently over time. A person in their seventies is far less likely to give up their model airplane hobby whereas a nine year old is switching hobbies with every turn of the head. Age seems to concentrate the adherence of the mind to what it’s already familiar with.

This general trend of stickiness to concentrate over time is largely responsible for institutional rigidity. An excellent example is the study of psychedelic compounds. For decades this area of inquiry has been a taboo topic, one sloughed toward the law and hushed for fear of punitive association. But why? It goes to reason that anything that presents even the potential of danger should be highly researched and studied so that we understand exactly what the risks are, and furthermore, what hidden benefits might also lie in such areas. We follow this logic when it comes to other dangers, whether they be on the level of enemy countries or sports teams - we study to minimize risk and search for leverage. And yet, the mental model that’s been applied to psychedelics has been one of denial and ignorance. It’s required the aging out of an entire generation for the topic to finally come back on the table of serious inquiry as spear headed by John Hopkins’ Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research.

Younger minds come in that still retain a diversified stickiness and replace the entrenched stickiness of older minds that have yielded the power to steer institutional agenda. That diversified stickiness allows for shifts in institutional agenda before things solidify again and the need for another generational rotation is required.

This concentration of stickiness in the mind is important in order to get anything done. It’s similar to attention and focus. If a mind has maximally diversified stickiness then it gets easily distracted, like children, and it’s absolutely necessarily to drill down into a topic for an undistracted amount of time in order to make progress on it. But, if the tendency to drill down on a useless topic or to drill down on a good topic in a useless way becomes the norm, then again the generational rotation is required to refresh perspective.

These are, of course, generalities, and when we drill down into specifics, there are crucial exceptions. The shift around psychedelics is an example ripe with appropriate coincidence. The shift was super charged, and perhaps initiated when the New York Times bestselling author Michael Pollan -who is most closely associated with writing about food- released a book all about psychedelic compounds. At the time of publication Pollan was in the ballpark of traditional retirement age - not exactly the sort of person with such esteem you’d expect to drop a serious discussion of such a taboo topic.

The topic of psychedelics is particularly pertinent to this discussion because of the effect psychedelics have regarding the mind’s stickiness. If we were to attempt to translate the concept of stickiness into the world of neuroscience, one possible candidate for real analogy is something called the Default Mode Network. This is a large scale brain network composed of a number of brain regions and is generally associated with an idea of self, narrative, memory and ideas for the future. From a crude bird’s eye view it might be summarized as the story we continually tell ourselves about who we think we are. Psychedelics in general, but particularly with psilocybin reduce activation of the Default Mode Network, and studies published in Nature earlier this year conclude an increase in emotion and brain plasticity. To be sure, these topics are only crudely understood. Hence the need for further study, and though the term here employed, the so called stickiness factor grossly simplifies much human experience contained in these topics it’s usefulness is in the potential to describe the utility of such compounds and topics that were previously considered dangerous. These compounds, which have been used since before recorded history, alter the stickiness factor of a person’s mind, greatly during the time of use and with a subtle lasting effect that an individual can capitalize on in beneficial ways. Again, this is a gross simplification of a topic that lacks specificity.

The trick we as a species doen’t seem to have figured out yet is how to have a conscious control over the concentration or diversification of our mind’s stickiness. The process of siloing the power of the mind’s stickiness into perennial topics is, from a very real angle, a bit of an imprisonment. We are left constantly yearning for a greater, deeper experience - the one that we seemed to be immersed in as children, but we fall for false advertisements of peak experiences that turn out to be counter-productive and lacking all fulfillment: the sugary ones in our diet and the vicarious ones on the screen. The greater, deeper experience isn’t something that happens to us necessarily. Probably the better way to capture this is to phrase the greater and deeper experience as simply a perspective we can arrive at, achieve and inhabit. The treasure of childhood lost is a perspective that has been narrowed and boxed out by what we’ve repeatedly added to that perspective. In a very real way, our sticky mind grows stuck to a certain idea of the world, shackled and then eventually oblivious to the potential experience and benefit of new perspective. For the most part, the crucial ingredient of experience that most often gets boxed out with a mind growing stuck is a deep sense of the moment. We live in our head, concentrating on ideas we have of the world, blinded from what is actually happening, and so the present has for many the dull veneer of something laboriously remembered the day after as opposed to the fresh vibrancy that is always available now.

DIPPING & DIVING

December 30th, 2020

It requires a bit of luck to know when to miscalculate. As we get to know ourselves better, it can become a skill to know when it’s wise to proceed carefully or dive right in. Mayfer’s Law outlines the second: The miscalculation of time required for achievement enables the undertaking of endeavours far larger than we would knowing attempt to achieve. The mechanics of this law are buried in the sunk-cost fallacy: once we get going on something, there is often momentum against some potentially wiser considerations to stop. But when is it wise to proceed carefully?

Seems like a strange question: isn’t it always wise to tread carefully? It’s de facto wisdom only because it’s rare: we’re really good at jumping into the deep end without first dipping a toe to test for temperature. Or so it seems. The de facto wisdom stands because we often dive right into the wrong things. Relationships, jobs, addictions..

Just go for it is the symmetrical wisdom to our de facto caution. But again, we misapply known wisdom: we often fail to take the advice when it’s applied to the right thing: starting that company, writing that book, learning an instrument. With those things we’re cautious, but for reasons that lack wisdom.

Learning how to learn hinges on a self-awareness of emotion, and how to foster the correct emotions with the right amount and frequency of new material. It’s imperative to be mindful of the tension between one’s own interest and frustration while exploring a new field. The first has to be stoked as much as possible, but it is always at risk of being snuffed out by the second. This is a spot where caution is best implemented: be cautious when frustration starts to rise - like a poison, it doesn’t take much to kill off an infant effort. Caution doesn’t mean stop, but merely to tread carefully, to tread mindfully and look for the next best place to dive in.

WANDERING COLLABORATION

December 29th, 2020

This episode is dedicated to The Visual Monkey who you can connect with on twitter with the handle @TheVisualMonkey

The discovery of the new will always look like wandering before it is found. This is one of the 9 principles of Tinkered Thinking. It’s a more direct equivalent to the catchier, albeit vague: think outside the box.

Perhaps the thought has crossed the minds of a few upon first hearing this catchy dictum: what exactly is the box, and why is my thinking inside of it? Presumably, the box is what is already known, what has already been discovered, created, decided upon and further more depended upon. The thinking that is characteristic of the box is old and therefore merely repeated by default. Getting out of the box means to abandon the safe haven of predictable patterns and to risk venturing into the unknown in order to have a chance at finding something new. The box is the mapped area, and because it’s mapped and structured, we already know what’s there, it’s the unmapped area that holds new treasure.

But how exactly do we navigate the unknown? The attempt to answer that question is one of the fundamental reasons why Tinkered Thinking exists, and while it’s imaginable that we might be able to codify some basic navigational principles regarding our venture into the unknown, it’s probably safe to assume the first step in such a process: wandering.

You’re only lost when you can’t find a place you know exists. We wander when we search for something that may or may not exist.

Now here’s a place or rather a thing that might exist: is it possible to come up with a simple visual illustration of this principle of wandering from Tinkered Thinking?

This is the question asked by a new Twitter account with the handle @TheVisualMonkey who later approached Tinkered Thinking with a preliminary sketch.

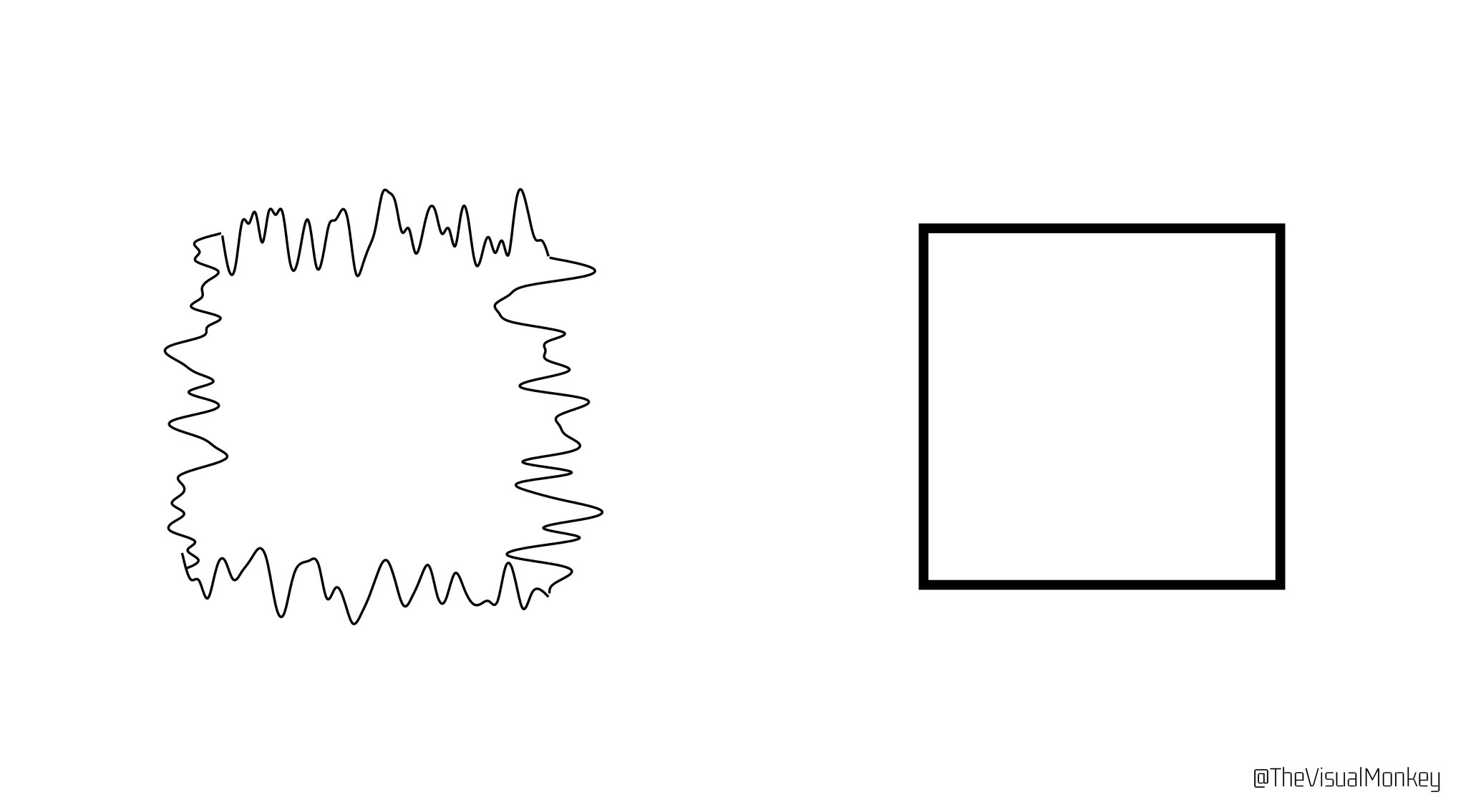

That first sketch showed a square and a second quasi-square represented by a wandering line that roughly approximates the shape of a square. The relation to principle of wandering is evident, but the illustration on it’s own doesn’t evoke the same idea - it’s up to multiple interpretations.

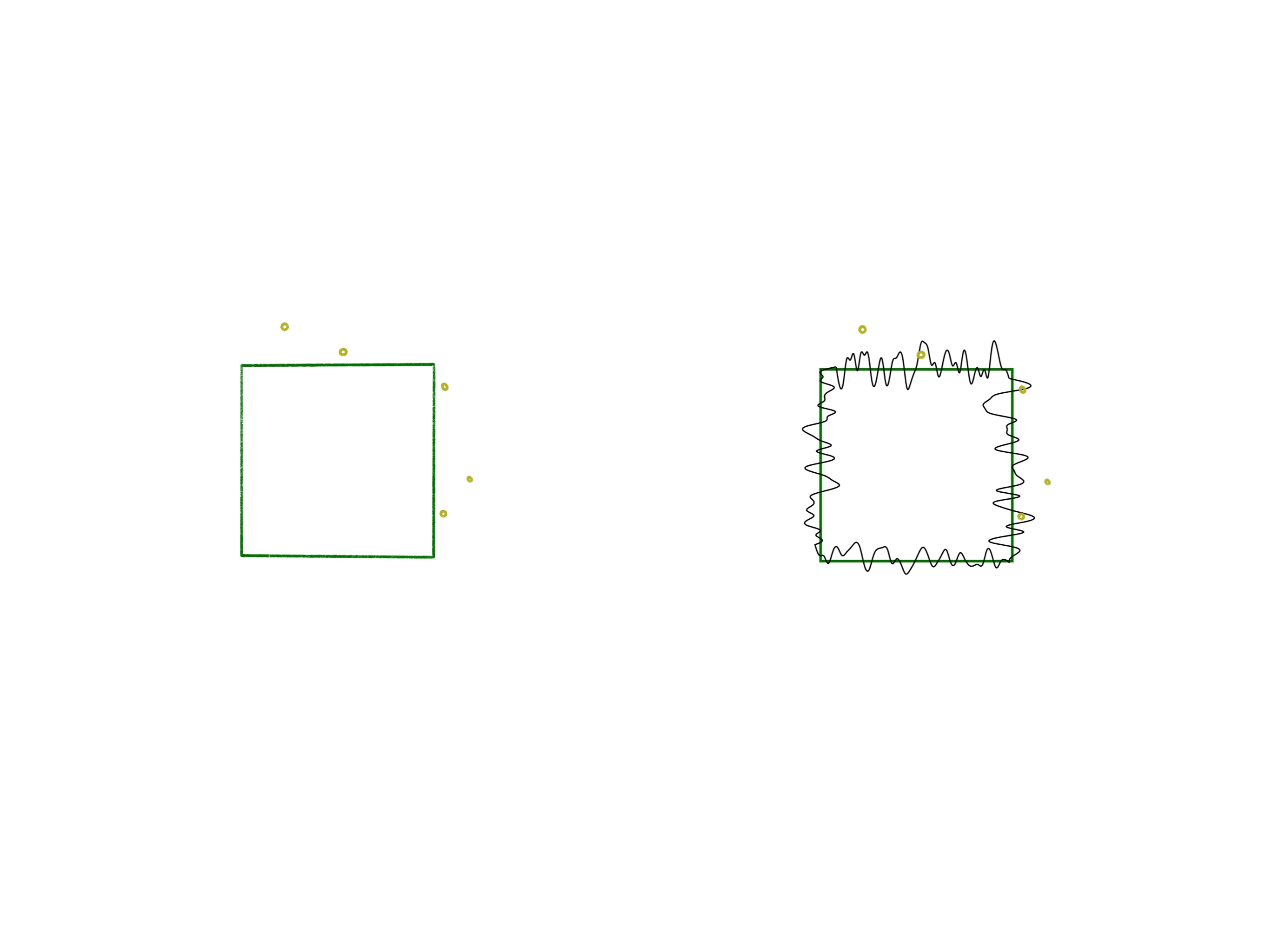

So a collaboration began and we wandered around for a better answer to that question about whether the principle could be illustrated successfully. Tinkered Thinking put forth an alteration of the design as a suggestion which shows the wandering line hitting specific points outside of the initial square.

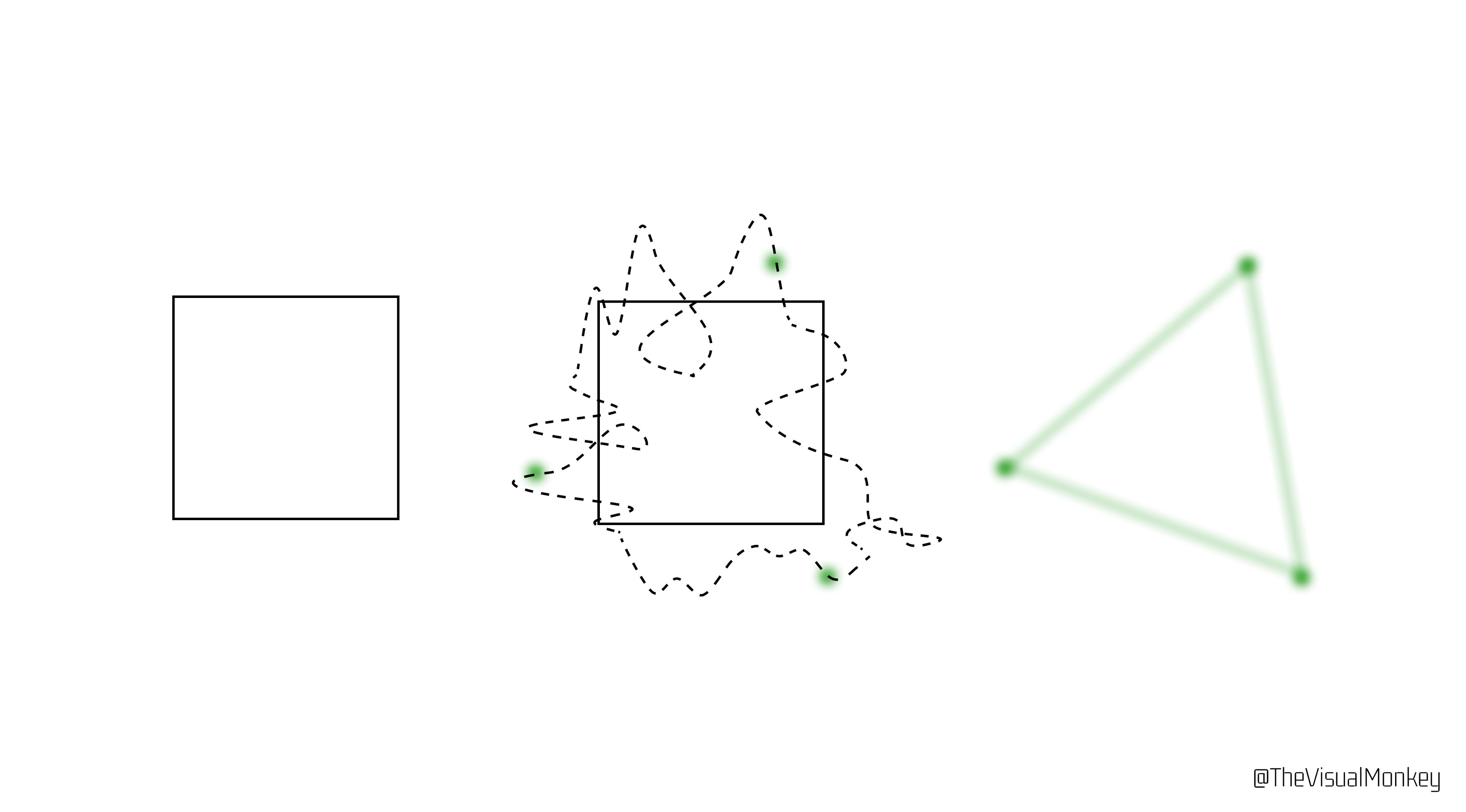

This progression seemed to be the needed step to answer that question. @TheVisualMonkey built upon the design and brought the idea to full fruition with an illustration displaying two squares, the second which has an overlay of a wandering line crossing 3 points, and then a third part of the illustration that shows the perfect triangle discovered that connects these three points in the absence of the square and the wandering path that was required to find the triangle. Wonderfully, the final illustration evokes the very process that was taken to find it. We had to wander around and poke at different ideas before we found what we liked.

A huge and humble thanks to The Visual Monkey.

-compressed.jpg)